Open Source and Open Science in Latin America

Authors: Laura Ación, Gonzalo Peña-Castellanos, Fernando Pérez

Translated to Spanish and Portuguese by Laurel Ascenzi y Melissa Black. Images: Julián Buede

This post is also available in Spanish and Portuguese.

CZI Blog abridged English version

Community and cultural context

This post is an extended write-up of a panel held during the 2021 CZI Essential Open Source Software for Science (EOSS) meeting, with Laura Ación and Gonzalo Peña Castañeda, moderated by Fernando Pérez. We’ve added some additional context and we cover a few topics that we were not able to get into during the panel due to time constraints. We had originally prepared these notes prior to the panel, and felt that it would be valuable to share them in full.

Our motivation for this panel, at the invitation of the CZI Open Science team, was to explore various aspects of the Open Source and Open Science development processes and communities in Latin America, more specifically in Argentina and Colombia, which are the countries where we have the most direct experience. Like other areas in science and technology, Scientific Open Source development tends to be dominated by activity originating in North America and Western Europe. But for us (who all hail from these two countries), its real promise lies in offering not only access, but agency as first-class participants and co-creators, to people from all nations.

This is a rich and complex topic, one that deserves both discussion and study. We are only three practitioners, so we present these ideas merely as a starting point for a conversation: our perspective is limited to the slices of our own countries we know well (Latin America is a large, rich and diverse continent with huge cultural diversity!), and we don’t pretend to generalize. But we hope it serves to open the discussion around how we can better make the development of Open Source and Open Science a more global endeavor, where all cultures are truly welcome as equals.

Localization and the role of English as interchange language

Question: Both of you addressed language localization as a tool to broaden the reach of Open Science in Latin America. However, translation is a laborious process and we know that scientists ultimately need to be fluent in English. Could you discuss why despite these issues, you still support the need to translate tools and materials from English to other languages?

Laura: Because, until we all can afford the time and money to learn English, I see no other way to make science inclusive. The world is missing out on learning from each other massively because, even these days, when a few people are flying to space as tourists, we still let the language be a barrier to learning from each other. I know that considering only English as the scientific lingua franca makes humanity miss out on massive amounts of knowledge. A toy example: language interpretation is affordable for conferences organized in high-income countries. Language interpretation would allow choosing from an enormous pool of new, fresh, and brilliant speakers for meetings and events if we were more open to interpretation to English and captioning. In Latin America, we rely daily on high-quality captioning in Spanish or Portuguese to watch movies or sitcoms. Reading captions is a relatively easy habit to incorporate with a huge impact to make room for learning from the valuable work of those not at ease sharing their knowledge in English.

Gonzalo: Well, scientists before becoming scientists are people, and are children, and the passion for research discovery and innovation is something that we can start very early. Even if our countries are lagging behind English literacy, there is no reason to lag behind in technology, programming, data literacy. The argument of a scientist must know English, then no need to translate anything is strong but is also exclusionary to anyone not a scientist, and we want to increase science literacy, advocacy. Take the Django Girls example, as a man working with that project, organizing and mentoring I often get asked why it needs to be only for girls, that is sexist, that is exclusionary. Well, the truth is that it is a temporary hack, in an ideal world we should not need to make the difference, but until we get there we will keep using and needing hacks.

Barriers beyond language

Question: In your experience, in addition to the language barrier, what other barriers exist for the development of Open Source and Open Science communities of practice in Latin America?

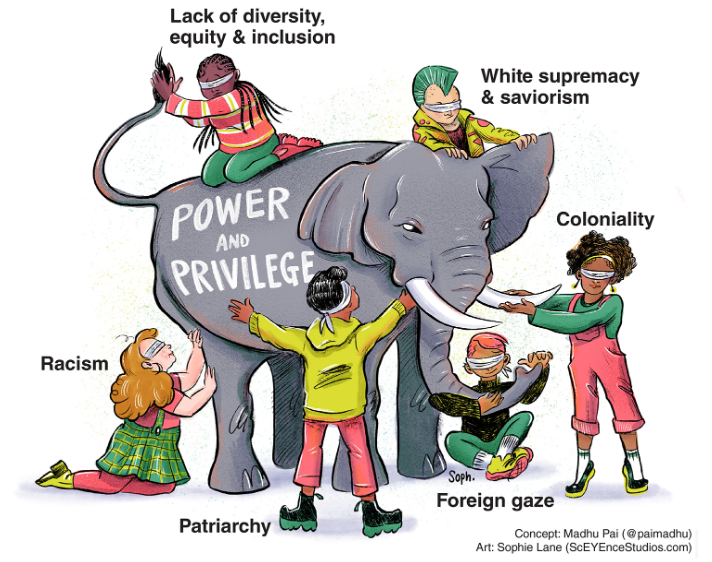

Laura: The current power and privilege asymmetry between Latin America and high-income regions is the main barrier. In the end, it all boils down to money or time. While the status quo shifts to dismantle centuries of injustice, investing in educating the existing and new generations (starting where we are in each geography) is the way to put Latin America on the map of Open Source and Science. Planting initiatives from more favorable geographies in Latin America is challenging because they do not translate well; often, the jargon is difficult to explain or translate. The number of blind spots folks outside the territory have is often mind-blowing to local folks. When you live in Latin America, the problems are obvious, but they are difficult to grasp when you are not in the territory anymore. I guess it all comes down to how hard it is to step into another person’s shoes. Thus, it is critical to have local persons with a history of advocating for the collective good at international decision-making tables. They will have a better understanding of what ideas click locally and which don’t. The more there is a dialogue between all geographies; the faster all barriers will fall.

Gonzalo: In basic infrastructure, lack of access to the internet, this means stable, reliable and with good speed 24/7 access. I think there are many efforts trying to work on issues but in the process the groups might specialize and not collaborate with other groups. It is not possible to have a unified body, but there should be some place (virtual/real) where all these initiatives can meet, work together. The crowdsourcing model has worked wonders for a lot of things, how could we apply this to increase cooperation among researchers. Another issue that might be more common on more senior academics is the hesitance to participate in general conferences (SciPy), because no memoirs, no index, no points for giving presentations there.

Regional events and the relationship with the broader international open source communities in R and Python

Question: You both organized, respectively, R and Python events in Latin America. Do you think the relationship with “the rest” of the Open Source world is where you’d like it to be? If not, what could be done, by either Python and R organizations, or companies like Microsoft or RStudio, to better engage and create stronger global networks?

Laura: In the R world, since 2017, there has been a considerable increase of presence in the region, particularly in the academic side, where Latin American talent made it to keynoting in useR! 2021 in Spanish with live captioning to English. UseR! also offers tutorials in several languages in addition to English. Latin America is well represented in the R academic events. Since 2021, I have been crossing my fingers that going back into the in-person or hybrid modality, this level of inclusion will continue - with a doubtful result for the crossing finger method. What is still missing is a good representation of Latin America (and other historically marginalized geographies) in the decision-making positions that drive the international community. I heard folks say that there are no good-enough candidates, with enough R experience in Latin America to be at such tables. A way to end that limitation is to mentor folks one-on-one, in an expedited, meaningful, welcoming manner and offer a clear path forward to integrate them soon. I think the RConsortium is moving in that direction. I have not seen companies, except for some isolated individuals working for companies, moving toward a meaningful inclusion of Latin America. Companies have the most prominent wallets, so they could make a considerable difference by sponsoring regional efforts. My impression is that companies often seem to consider that swag, stickers, pins, food, or offering a meeting room for the event are enough to keep volunteers engaged and organizing events that give companies visibility. These are the cheapest marketing campaigns that I have ever seen, at the expense of volunteers. For meaningful inclusion, they need to switch from swag to compensate for volunteers’ time. I know it can be very complicated to transfer money in Latin America; however, that is the only way I see toward meaningful inclusion.

Gonzalo: Things have been steadily improving, but the problem with all the volunteer work is that it takes a lot of strain on you. A recurrent problem I have seen is the lack of generational replacement, that is, getting new blood and new faces to contribute to leading the communities. We can have all the support we want from different companies abroad but that does not solve the issue of local people in charge. Having paid positions for these advocacy jobs could be an option and larger companies have more and more of these roles. Making events is now easier as there is trust in the communities so sponsors keep coming back. Mentoring is also a great way to try to get new blood but it does take time also. It is undeniable the impact that Python growth has had in the past years. I have differences with the way some of the events and conferences are made, and we need to find what works for our own countries, but that also has to do with the values and objectives.

Institutional spaces: from the local to the global

In this section, we look at the spaces where this work develops, from policies to academic and industrial settings. Each of these contexts is quite different in our countries than in the US or Europe, and we will have a better chance of building healthy Open Source/Open Science communities if we engage the academic research and industrial development cultures in ways that meet their local needs.

Policies - implementation and roadblocks

Question: Are there public policies to promote Open Source and Open Science in your countries, or in other parts of Latin America? How are these policies implemented? Could you identify the greatest difficulties to carry them forward?

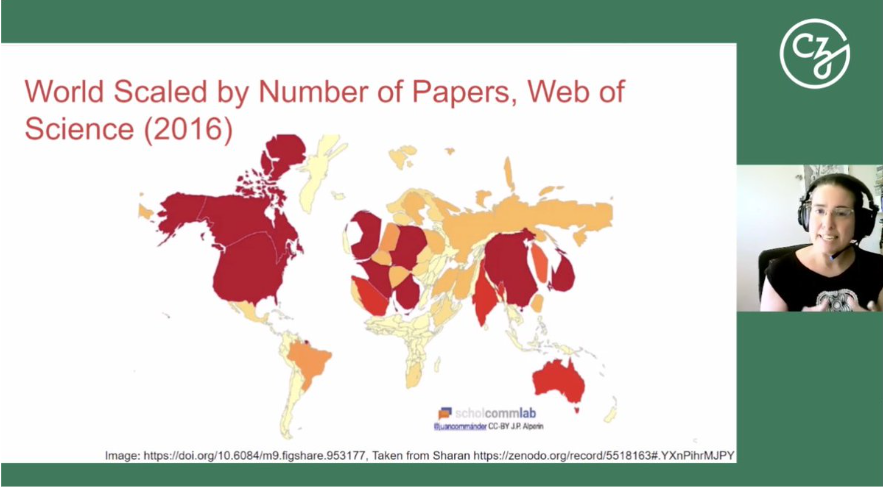

Laura: I don’t know much about public policy in these areas. I know there is a lack of incentives to go with Open Source and Science in academia in our countries. Thus, I suspect there are not many policies being enforced. A significant aspect is that even Latin American researchers for open data, code and science often voice their concerns about global asymmetry in Open Science. For example, it can take years to collect valuable data frugally, with vast amounts of hard work. The moment the dataset is open, a lab in a high-income region puts its ten highly skilled persons to analyze the data and write the papers from that dataset. Hence, as many of the discussions sparked by Open Life Science, the current paradigm of Open Science has systemic power and privilege asymmetry built-in, the elephant I show in this presentation. The primary barrier is the lack of candid conversations that end up in accountable actions to change the paradigm and dismantle the asymmetries. Of course, this is not a trivial or fast process because the problems are systemic to our societies. However, I see low-hanging fruit in democratizing the tools through accessible education. In Latin America this means, among others, free, in the local language, with local interest, addressing local accessibility needs. Another ripe fruit is the metrics. Until asymmetries are gone, we must change the system metrics. For example, by giving the same recognition in our systems to collect and maintain data, write and maintain code, publish a paper, or organize welcoming communities and events. These activities are crucial for Open Science and Source to thrive, yet only publishing the paper counts in academia. Also, I think we must give extra credit if persons do any of these despite systemic marginalization playing against them. In academic Latin America, we have decades of experience adapting international metrics to our region. For example, we index our regional journals to evaluate our scientists better using Scielo. We can teach other regions without experience adapting system metrics.

Gonzalo: Even before the pandemic the Colombian government has started making moves to improve data literacy and has offered many different programs to form different professionals with different backgrounds (Colombia 2.0, 3.0 and so on). This however seems to be aimed more at practicing professionals and not academics and scientists. Access to the internet in regions (recent scandal on providers of the wifi spots!). There are no laws enforcing or even promoting the use of open source technologies. Several projects started in the 2000s but were archived or the initial intent changed. Open data is becoming more of a thing.

Academia: from usage to participation and contribution

Question: Open Source has created new and complex relationships between academia and industry. I’d like to first ask you, how do you see the culture of Open Source and Open Science in your countries’ academic circles? I am particularly curious about the adoption, or not, of a culture of participation, contribution and leadership in Open Source projects and Open Science efforts, not only of usage and access (while that’s important too).

Laura: A very rough estimation, based on having gotten my Ph.D. in the US in 2011 and then transitioning to Argentina´s academic system, is that in Latin America we are as the US was a decade ago in terms of adoption, participation, contribution, and leadership in Open Science. Inclusive communities of practice that lower as many barriers as possible to international involvement, such as R-Ladies, PyLadies, Open Life Science, or The Turing Way, help to change this. But we need many more. Also, communities of practice will be a lot more effective if they start at least favored geographies and get to have international reach, rather than starting in high-income countries and getting global reach from there.

Gonzalo: Pandemic has been both a curse and a blessing, and in this aspect it helped propel a lot of things into the future. In my personal experience, having more open source contributors has been very difficult. We have a very big consumer mindset in that we consume a lot of open source tools, but we still need to make the jump to contribute and then make the jump to create. We probably need more sprinting, more visible faces and more incentives for people to contribute. I have been in contact with different professors from my university and some of them have started working with open source tools and all of their students are now using it. To be able to really make progress we need academic incentives for students and also for professors. Cost of software and tools is often not an issue as many universities get academic licenses. I don’t think we necessarily need more specialized groups for academics, we need more academics to participate in the already existing communities, but we hit the generalist/specialist problem.

Industrial engagement with open source in Latin America

Question: And next, I’m curious about the industry side. As more companies spawn from Latin America and have a wide reach. What could these companies do to support open source contributions - Globant, Mercado Libre, Rappi (to name a few)?

Gonzalo: With the advent of artificial intelligence, machine learning and in general data engineering and science a lot of these companies have a big need of hiring scientists to do applied research. On one side this is a good place for PhDs to migrate from academia, if this is something that interests them. On the other hand these companies do invest in research but do not necessarily follow traditional academic publication. On the other hand the publication model is broken (but that is a topic for another day)

- These companies are very big users of open source technologies and in some cases also creators of open source software. However much like we are still struggling to have big companies outside of LatAm to contribute in a more meaningful way to open source we are experiencing the same. Companies at some technical levels understand the value in contributing to open source but this needs to go up into the C-level and managerial levels so a true commitment to invest in open source is made.

- On the industry side and the community side, the work done by several members of the community, organizers, leaders of pycons has allowed the creation of very strong ties in sponsoring, and helping with events. We need to take the next step. We need to start sprinting on projects and I guess we need to be better marketers at why.

Question: How could ties between academia and these companies improve?

Gonzalo: I honestly lack information but in some cases there is active collaboration between companies and academia where MSc thesis are active case studies and developments. This seems to be more prevalent between private universities and industry. There is also the case of academics jumping ship into industry as academia in Colombia is often a difficult road to navigate.

- There should be a lot of opportunities for students to do internships in technology companies working and using open source software.

- A point of intersection is the work with communities so I see a lot of value in driving more academics into the open source communities so industry and academia can meet.

- Companies should probably invest more in R&D

- Academia could host more events where industry takes an active role, such as Tech Fairs / Science Fairs.

Question: And what is the “industry brain drain” situation in your country like? Do academics have the resources and opportunities they need, or are they flocking to industry after returning from abroad with advanced degrees? (you both are different examples of this)

Laura: I will start from the last to these three questions. Working in Artificial Intelligence (AI), I stay in academia in Argentina only because I can live without affecting my kids’ livelihood with less than US$ 1,000 per month that I make in my tenured, full-time academic position. If I had to pay rent in Buenos Aires, I could not get by with this salary. All data-based and computational disciplines are being deserted in academia because academic wages are not competitive. During the pandemic, teaching online made undergrad and grad education more accessible in Argentina and the region. We are seeing more people interested in higher education than ever. That is great news, except that it is not coming with additional investment in education to pay for instructors and, it is even worse for computational skills educators. In conversations with academics who recently switched to working in the industry, I have learned that the only industry incentive is maximizing profit. In responsible AI, changes are driven exclusively by regulations and demands from clients with big wallets. I guess that for Open Science and Source it is pretty similar. Policymakers and the public agenda have a significant role in asking tech companies to join the efforts to go open. On the other hand, academia is conservative and tends to mistrust industry and fast changes. Lowering administrative barriers for the industry to collaborate with academia would help. Also, purely altruistic ethics in the industry with no hidden plans for maximizing profit or merely image washing would help build trust and drive change. However, is it realistic to ask and expect that industry is truly altruistic? I do not think so.

Gonzalo: Although I am not part of academia, I do have contact and follow different academics in different networks and during the course of the past year I have seen many cases of people that moved to industry, (Mercado Libre for example). When I stopped my PhD was because I was not happy with what I was doing but also in pursuing it I always wondered what would I do when I go back to Colombia as it was always something I wanted to do. Short answer, do academics have the opportunities and resources they need? The majority does not. I do not know if I would say the flock, which feels like an active attempt at moving, the reality is that PhDs have to look for different opportunities and being scientists, migrating to be a Data scientist is an option. Not that these PhDs do not enjoy their new life as data scientists, but many landed there because there was no other choice. I have also seen PhD graduate students migrating to software engineering.

Growing Open Source Science as a global endeavor

Question: What are concrete ways in which we can make Open Source and Science genuinely global?

Laura: Many experts in Open Source and Open Science in Latin America are open to collaborating. Reach out! Let’s talk!

A longer answer:

- Collaborations could include applying for grants or sponsorship together, contracting jobs to develop training materials, consulting services from experts in the territory, or evaluating if what you think is inclusive for Latin Americans is actually inclusive. The disabled people and people with disabilities mantra of “nothing with us without us” works perfectly for Latin Americans, too. Having consultants living in the territory is crucial because it is easy to forget how day-to-day life is in Latin America when one moves to more favorable geographies.

- Fund more incubators such as CS&S that give access to pots of money usually unavailable internationally and provide all the infrastructure to execute them.

- Fund more talent-leveling organizations such as Open Life Science or MetaDocencia. We need more on-ramps programs teaching open leadership, community building, and working openly in Open Science.

- Pay for the time of local folks to learn the Open Science and Open Source state-of-the-art. Make those learning materials accessible by having them in local languages.

- If you are overrepresented, make room by offering your seat at decision-making tables to historically marginalized folks. You can also condition your participation to marginalized folks joining and staying at the table. If you are overrepresented, ask to mentor marginalized folks to these positions by shadowing you.

- Advocate, so the metrics used to onboard folks to decision-making spaces adjust well to marginalized realities. An excellent source for rethinking metrics is Rowland Mosbergen’s work which proposes quantitative approaches to intersectional equity.

- When informing and changing your metrics, ask marginalized folks how to do this and pay them for their time.

- Do not assume marginalized folks will work for free. Also, be aware that they may accept to work for free because of the scarcity of opportunities open to them. However, this quickly leads to exploitation due to power and privilege asymmetries.

- Start treating marginalized folks you invite to your thing as you would treat a Nobel Prize winner in your field. Always assume you have a lot to learn from others.

- Last but not least, if you want to have a diverse global audience in your event, lower the economic barrier. Always offer a free ticket option, no questions asked. It will be more work for organizers because you can expect a 70% no-show rate for free events. Avoid as much as possible reimbursement processes or applications for waivers or scholarships. These put extra work on the shoulders of those whose time has been historically wasted the most already.

Gonzalo: Short answer: It is hard.

A longer answer:

- For traditional education programs, we need ALL curriculums to include an introduction to programming. Much like English is a need, programming literacy is also one.

- We need bilingual education from primary school all the way up.

- We need full infrastructure coverage.

- We need funding bodies to also fund research devoted to the creation of software as the main goal.

- We could ask governmental mandates to enforce, promote, and encourage the use of open source tools at all organizational levels.

- We need to unify efforts across the continent, not only by collaborating in research and research grant applications but at the community level.

- Until we reach full English literacy we need to make science local, so the other way around, and in this space there is a lot of room for science advocates.

- Before we can make things global, we need to make it local.

A closing thought: creating tools and knowledge for our needs

Our world is highly interconnected, but while a tweet can be read instantly across the planet, active engagement in the creation of the computational infrastructure that underpins science remains unevenly distributed. Countries like ours are sometimes constrained by a narrow view of science, where chasing classic metrics of academic prestige (such as publications in high-profile journals) is over-optimized for.

For us, the key promise of open source science is not access to tools or knowledge free of charge, but participation in the creative process that is open to all. And while the basic tenets of scientific discovery transcend boundaries, local context is critical when it comes to actually understanding the world we live in. Our countries face challenges where the tools of global science are of critical importance, yet we need those tools to adequately represent our reality. From climate models that correctly resolve local topography to biological and biomedical databases with proper representation, in all domains we need scientific knowledge to meet our specific context.

We can create that knowledge if we have equal agency in shaping the tools of science itself. We hope these notes contribute to a conversation to make open source science a more global endeavor, open to all.

The authors

Laura Ación

Laura Ación is a Research Scientist at the National Research Council in Argentina, where she leads a multidisciplinary artificial intelligence and data science co-laboratory. With a Ph.D. in biostatistics from the University of Iowa, she works on topics ranging from the de-identification of electronic health records to using machine learning for nanoparticle design, and various other projects related to addiction. Her group pushes for the responsible use of data, including open science and reproducibility in their research, but she also trains the next generation of scientists in these practices. She was an instructor and trainer for The Carpentries and co-founded MetaDocencia, a Spanish-speaking organization inspired by the Carpentries. She is also a community leader, having co-founded R-Ladies Buenos Aires, R en Buenos Aires, and LatinR, a Latin American R conference. She was also the first non-founder promoted to R-Ladies Global Leadership team and was involved in the organization of useR!.

Affiliation: MetaDocencia e Instituto de Cálculo - UBA - CONICET, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Gonzalo Peña-Castellanos

Gonzalo Peña Castellanos is a Colombian Civil Engineer with an MSc. in Hydroinformatics and an MSc. in Sanitary Engineering. Having initially worked with real time flood forecasting and downscaling of General/Global Circulation models for urban applications, he discovered a passion for Software Development and Data Science which led him to collaborate in different open source projects and to eventually join Anaconda, Inc and currently Quansight, Inc as a Senior Software Engineer. Today he is a JupyterLab Core developer, working on localization and internationalization, and a core contributor to the napari project, with experience in desktop, frontend and backend development. Gonzalo is an active member of the open source community contributing to different projects as a member of the grants working group in the Python Software Foundation and a leader in the Python Colombia Community helping shape and organize communities such as Django Girls Colombia, Python Bucaramanga, the national and Latin American Python Conferences, PyCon Colombia and SciPy Latam and more recently, the Python en Español community.

Contact: gpena@quansight.com, perfil en LinkedIn.

Affiliation: Quansight, Bogotá, Colombia.

Fernando Pérez

Fernando Pérez is an Associate Professor in Statistics at UC Berkeley and scientist at LBNL. He builds open source tools for humans to use computers as companions in thinking and collaboration, mostly in the scientific Python ecosystem (IPython, Jupyter & friends). A computational physicist by training, his research interests include questions at the nexus of software and geoscience, seeking to build the computational and data ecosystem to tackle problems like climate change with collaborative, open, reproducible, and extensible scientific practices. He co-founded and co-directs the Eric and Wendy Schmidt Center for Data Science and Environment at Berkeley DS4E. He is a co-founder of Project Jupyter, the 2i2c.org initiative, the Berkeley Institute for Data Science and the NumFOCUS Foundation. He is a recipient of the 2017 ACM Software System Award and the 2012 FSF Award for the Advancement of Free Software.

Contact: fernando.perez@berkeley.edu, @fperez_org.

Affiliation: UC Berkeley, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Project Jupyter, 2i2c.org.