Communities of Practice and Their Influence on the Dissemination of Open Science in Latin America

When we talk about Open Science, we refer to practices that seek to ensure research transparency by sharing the workflow’s various stages. In 2021, UNESCO approved the Recommendation on Open Science to promote global consensus on its importance (Beigel, 2022) and its key pillars: open scientific knowledge, open scientific infrastructures, scientific communication, open engagement of social actors, and open dialogue with other knowledge systems (UNESCO, 2021).

One possible instrument for the dissemination of open science, potentially with more acceptance from users and a regional perspective, are the communities of practice, which, according to Etienne and Beverly Wenger-Trayne (2015), are self-organized and self-maintained groups of people who share a concern or passion for something they do and learn to do it better as they interact regularly. In recent years, these communities have grown significantly in Latin America, many focusing on reducing the gender gap in STEAM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts, and Mathematics), such as R-Ladies, PyLadies, GeoChicas, LasdeSistemas, TecnoLatinas, and Women in Bioinformatics and Data Science Latin America. Others aim to transmit skills for teaching computational tools or are dedicated to teaching open science tools and practices, such as MetaDocencia.

In this context, what is the role of communities of practice in the dissemination and implementation of Open Science practices in general, and specifically, in the Latin American region?.

Social networks are communication platforms that have allowed scientific communities to extend the reach of their ideas and research work. According to Mathilda Åkerlund’s work (2020), online platforms provide opportunities for participation and inclusion and offer people new personalized ways to manage their identity, relationships, and information.

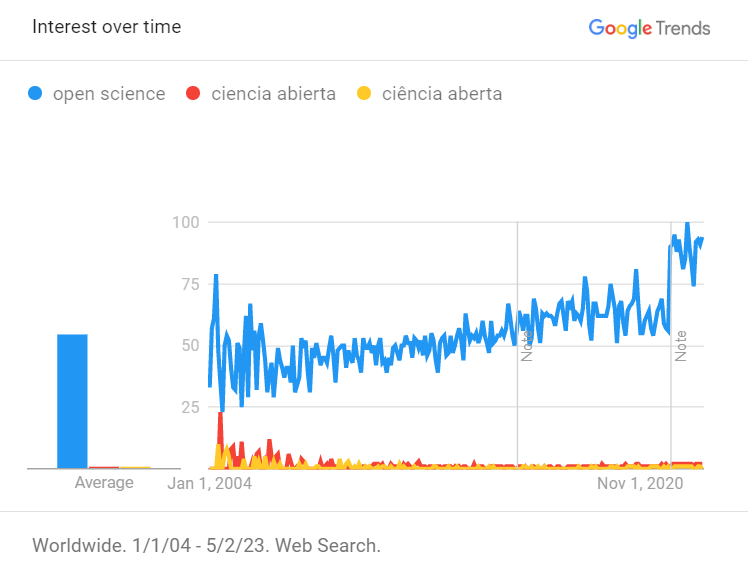

We used two methodologies to analyze the effect of communities on the dissemination of open practices. First, we conducted an exploratory analysis of the evolution of searches for the terms “open science,” “ciência aberta” (Portuguese), and “ciencia abierta” (Spanish) from 2004 to the present (Figure 1).

Evolution of searches for the terms “open science,” “ciência aberta” (Portuguese), and “ciencia abierta” (Spanish) from 2004 to the present

Source: Google Trends.

At first glance, Google Trends searches show that interest in the use of the terms “ciencia abierta” and its Portuguese version over time in Latin America is still incipient and lags far behind the conceptual development of the term “open science” used in the Global North. The breakdown by region shows that the term in Spanish is more used in Colombia, Mexico, Venezuela, Argentina, and Chile. Meanwhile, its Portuguese version concentrates on searches in Brazil.

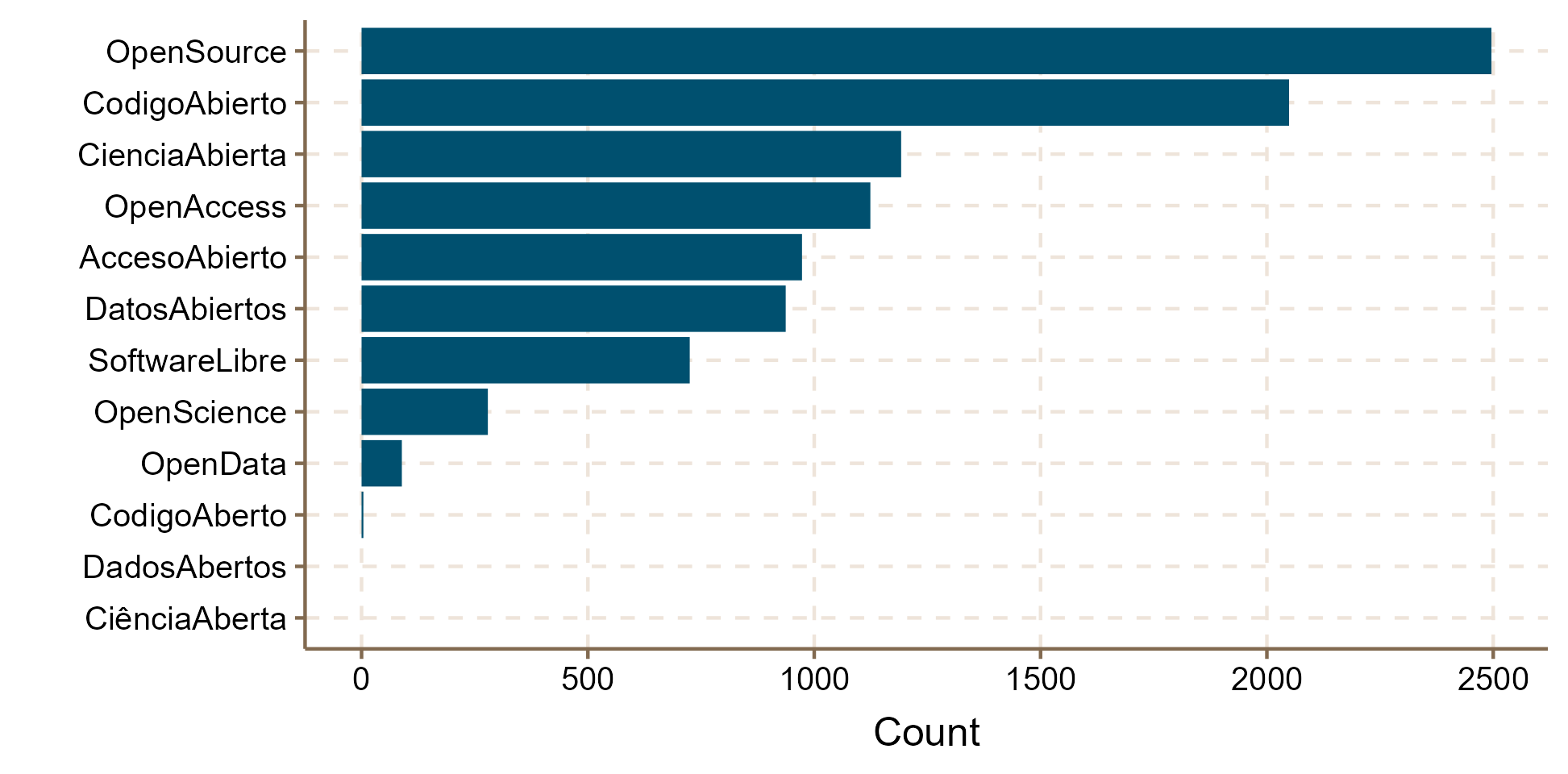

Second, we conducted a social media analysis to identify influential users and user groupings and study their association with communities of practice. For this, we conducted a search for tweets that mentioned at least one of the terms listed in Figure 2. From the collected tweets, we found that the top 3 terms used are Open Source, Código Abierto, and Ciencia Abierta. We filtered the original results by language (Spanish) and location (Latin America) and excluded accounts from government organizations and commercial accounts.

Figure 2: Terms used for tweet search and their frequency of use. Graph showing the search terms in tweets.

Fuente: own elaboration.

Fuente: own elaboration.

The final result included a sample of 2,119 tweets generated by 1,423 different accounts and retweeted 7,405 times by 4,733 accounts. Finally, we analyzed each user to identify whether the account belonged to a community of practice.

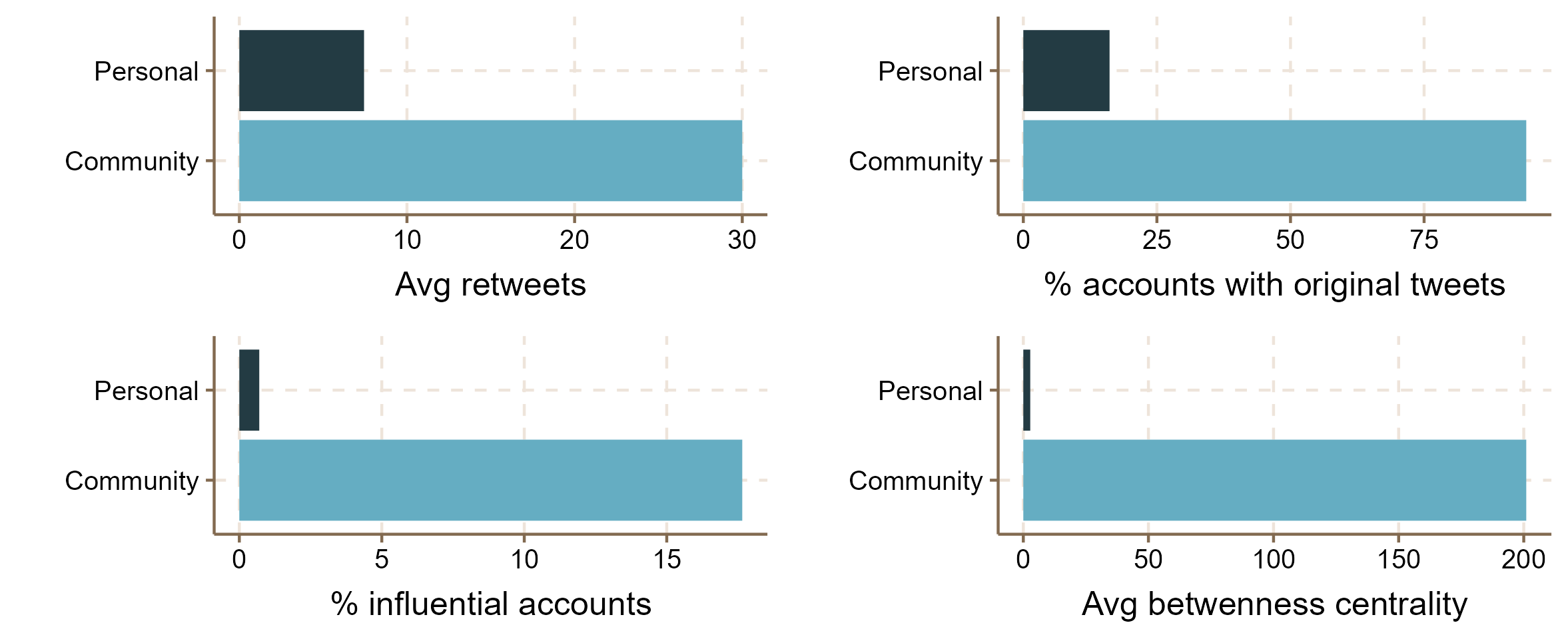

For the network analysis,we included each user or account as a node and each retweet as a link for the network analysis. Then, we calculated various metrics for personal accounts and community accounts (Figure 3):

- Average retweets.

- Percentage of original tweets.

- Percentage of influential accounts (> 20 individual users who retweet it).

- Average betweenness centrality (the number of times a node is on the shortest path between two other users).

Figure 3: Terms used for tweet search and their frequency of use.

Source: own elaboration.

Source: own elaboration.

The results show that accounts belonging to communities generate more original content related to open practices than personal accounts, and, in turn, their posts are more retweeted by various users. Additionally, we found that community accounts often act as a nexus between many of the users of personal accounts included in the study. All these measures speak to the multiplier potential that communities of practice have to disseminate the concepts associated with open science and increase their reach and impact.

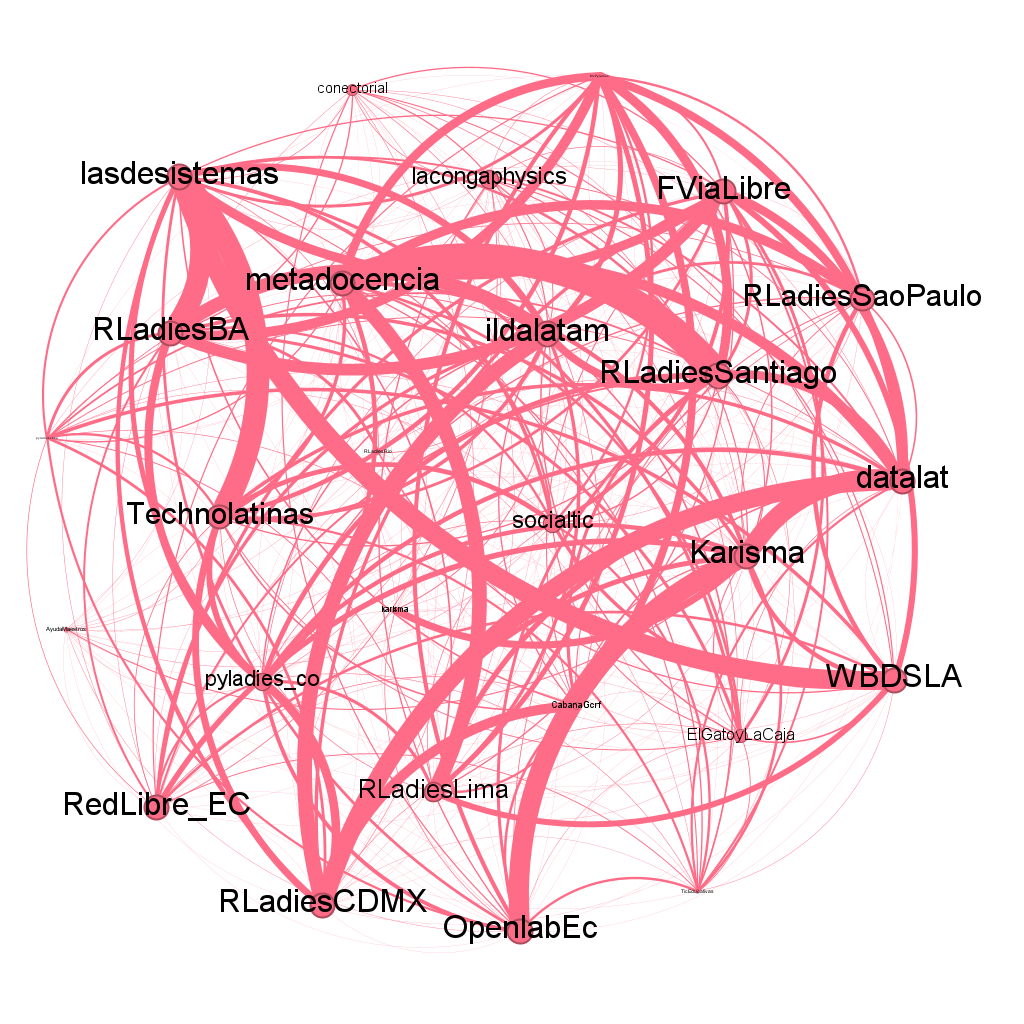

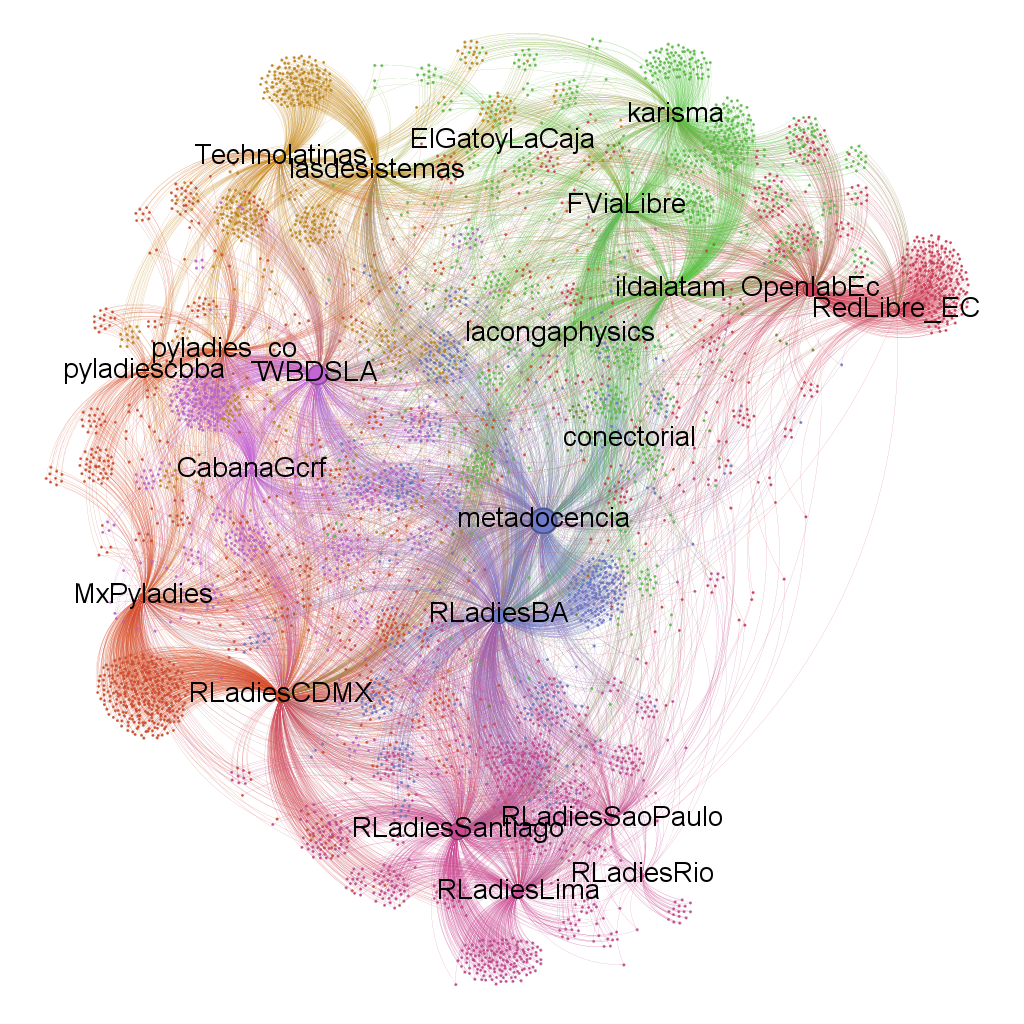

To analyze the relationships between the communities obtained in the previous sample and other Latin American communities identified earlier, we conducted a new analysis, taking communities as nodes and the followers they have in common as edges (Figure 4).

Figure 4. The graph shows the number of followers shared by the communities of practice studied through the width of the connecting curves.

Source: own elaboration.

Source: own elaboration.

Figure 4 shows that all communities are connected to each other by at least one user except Conectorial, a very young community that, while not connected to all, is connected to the majority.

Finally, we conducted a modularity analysis on a bipartite network with communities and their followers as nodes. Modularity is a measure of network structure that gauges the strength of the division of a network into groups or clusters. It involves grouping users in such a way that connections between them are more robust than connections with members of other groups. We will refer to each group of users as a cluster.

Figure 5: Network graph - Modularity.

Source: own elaboration.

Source: own elaboration.

In Figure 5, links between members of the same cluster are shown in different colors. Modularity shows that their connections are associated with their geographical location, as is the case with OpenLabEC and Red Libre EC, or MetaDocencia and RLadiesBA, and, in some cases, there seems to be a relationship between communities with similar purposes, such as Karisma, Via Libre, and ILDA Latam, which work on digital rights, governance, and ethical use of data, for example.

Despite the challenges we faced during the study due to restricted access to Twitter data following changes in the API usage policy, we can summarize the conclusions of this initial approach in the following points:

- High modularity is mainly associated with the community’s geographical location and the central subject of their work or purpose.

- We also observed a large number of common followers, indicating a network of users and participants fostered by communities of practice.

- The multiplier potential of communities is verified through the work of coordination and connection among users and topics.

It remains to be considered how much openness these communities promote or if they are restricted to the same realm of relationships (endogamy).

While platforms currently present complex challenges involving the transmission of a common good (knowledge) in private hands and corporate policies (Brembs et al, 2023), they are helpful for analyzing how communities of practice link and their role in disseminating open science. Therefore, we will continue to deepen the analysis to characterize them in our region in future works.

Sources

- Repository of used dataset: https://zenodo.org/record/7865273

- Presentation “Communities of Practice in Latin America and their influence in dissemination of Open Science” shared in the csv,conf,7 including speakernotes.

References

- Åkerlund, M. (2020). The importance of influential users in (re)producing Swedish far-right discourse on Twitter. European Journal of Communication, 35(6), 613–628. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323120940909

- Beigel, M. F. (2022). El proyecto de ciencia abierta en un mundo desigual. Relaciones Internacionales, (50), 163–181. https://doi.org/10.15366/relacionesinternacionales2022.50.008

- Brembs, B.; Lenardic A.; Murray-Rust, P.; Chan, L.; Irawan, D. E. (2023). Mastodon over Mammon - Towards publicly owned scholarly knowledge. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7652771

- Shalaby, M.; Rafea, A. Identifying the Topic-Specific Influential Users in Twitter. International Journal of Computer Applications 179(18):34-39. DOI: 10.5120/ijca2018916316

- UNESCO (2021). Recommendation on Open Science. Recuperado de: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000376130?posInSet=6andqueryId=c7ea2590-6b6f-4279-aae7-ed3e4c50616f.